Container Runtime

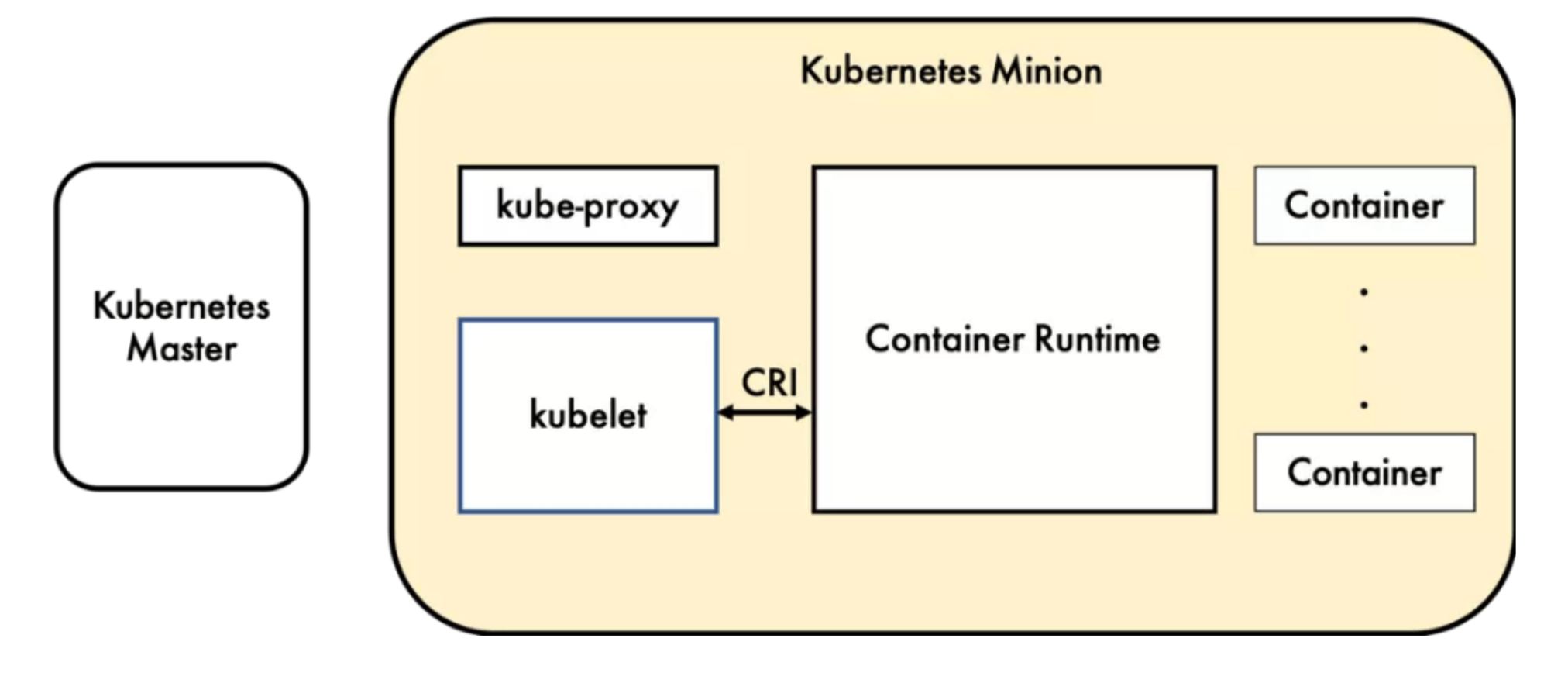

Container Runtime runs on every node in a Kubernetes (k8s) cluster and is responsible for the entire container lifecycle. Docker is currently the most widely used. With the development of container cloud, more and more container runtimes have emerged. To solve the integration problems between these container runtimes and Kubernetes, the community introduced CRI (Container Runtime Interface) in Kubernetes version 1.5 to support more container runtimes.

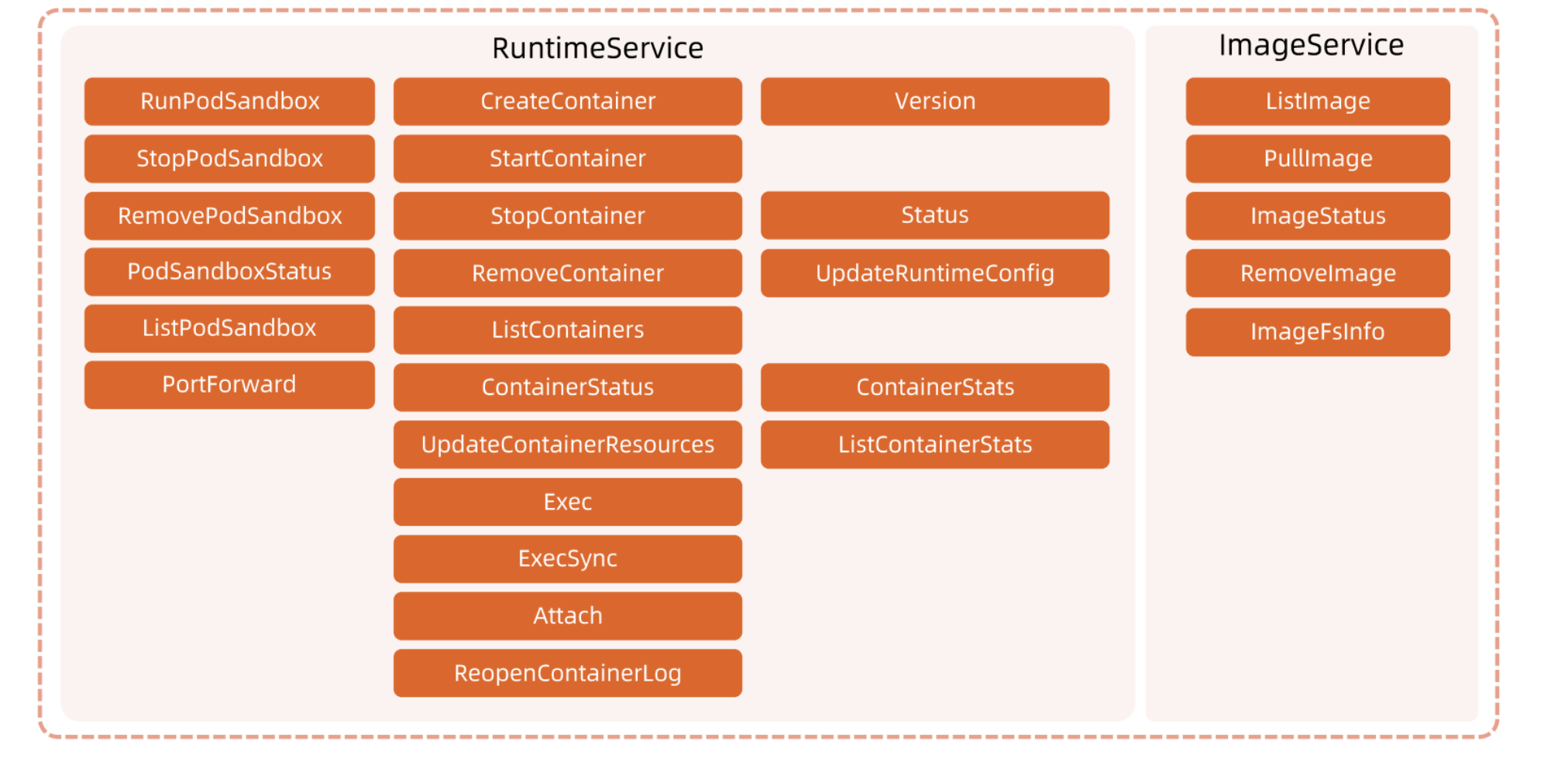

What is CRI

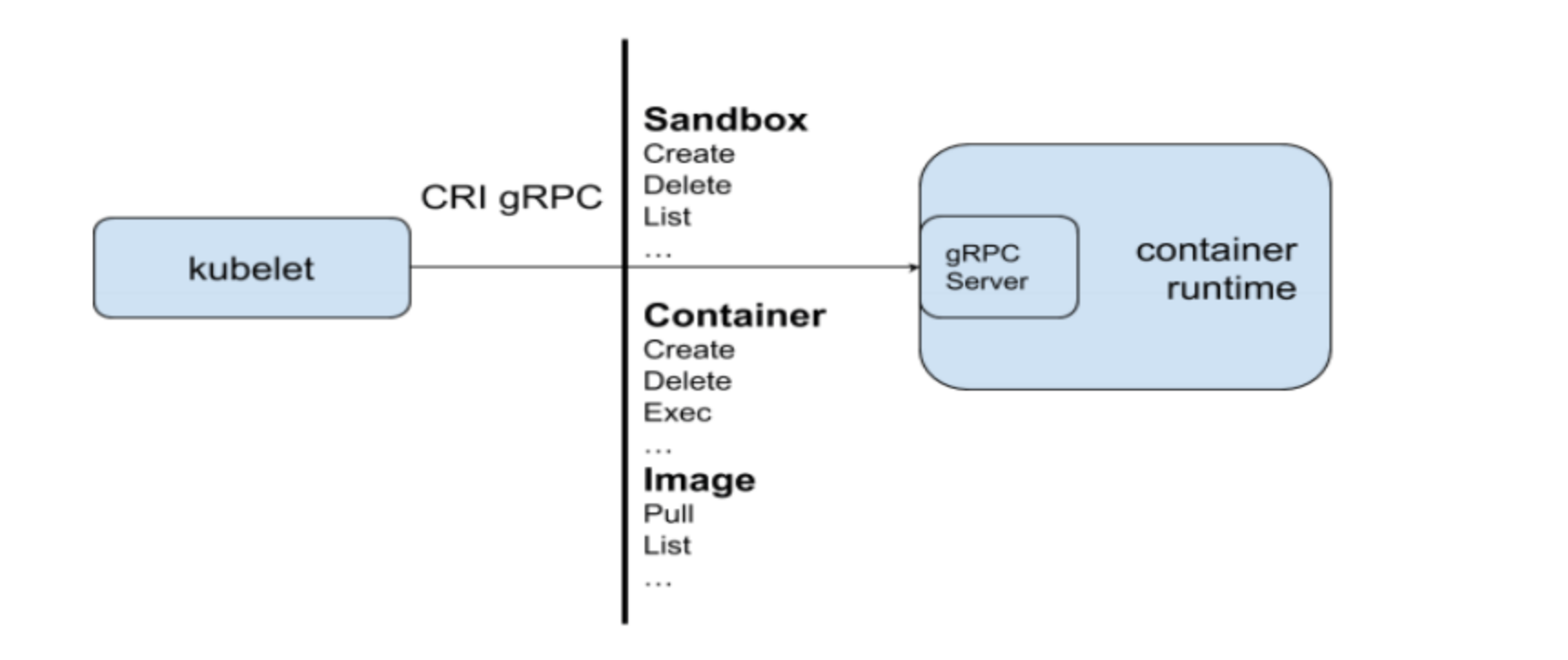

CRI is a set of gRPC services defined by Kubernetes.

kubelet acts as a client, communicating with container runtimes through Socket based on the gRPC framework. It includes two types of services:

- Image Service: Provides remote procedure calls for downloading, checking, and deleting images;

- Runtime Service: Contains remote procedure calls for managing container lifecycle and interacting with containers (exec/attach/port-forward).

Runtime Hierarchy

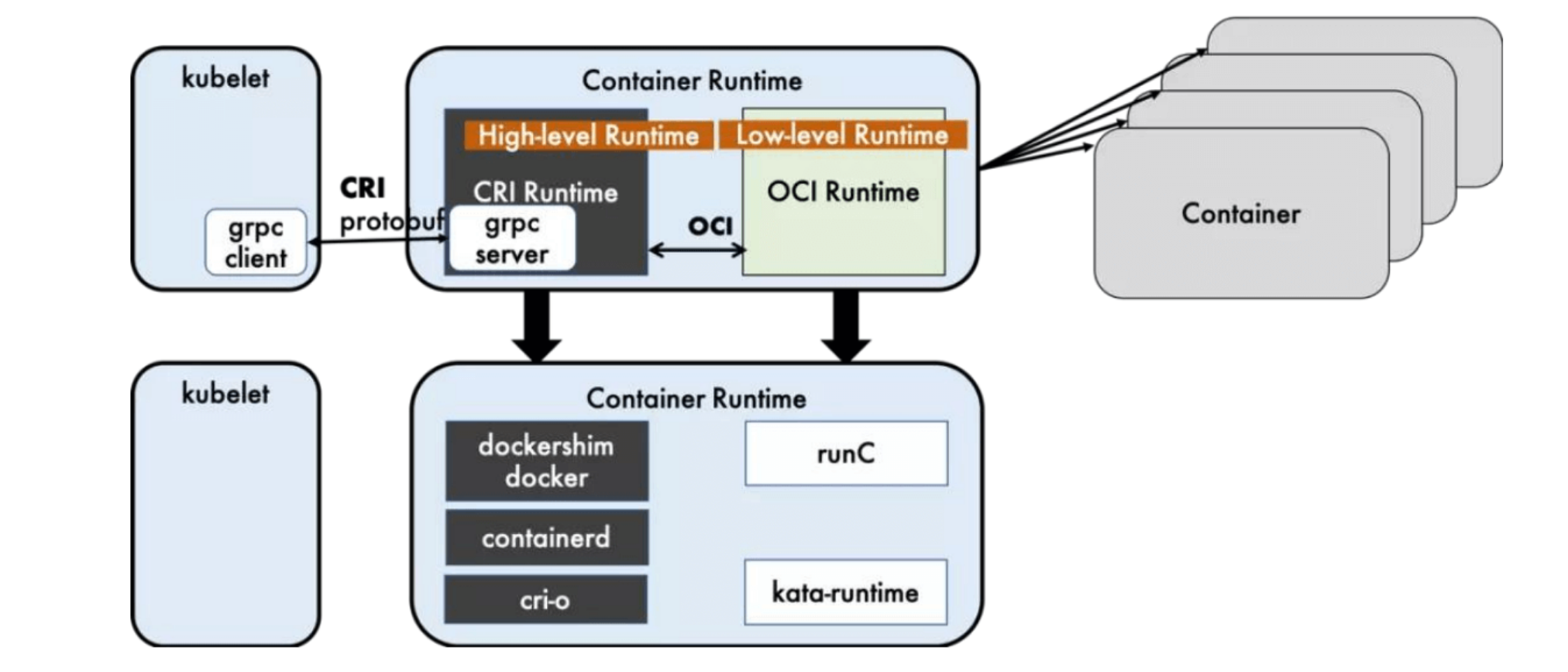

Container runtimes can be divided into high-level and low-level runtimes:

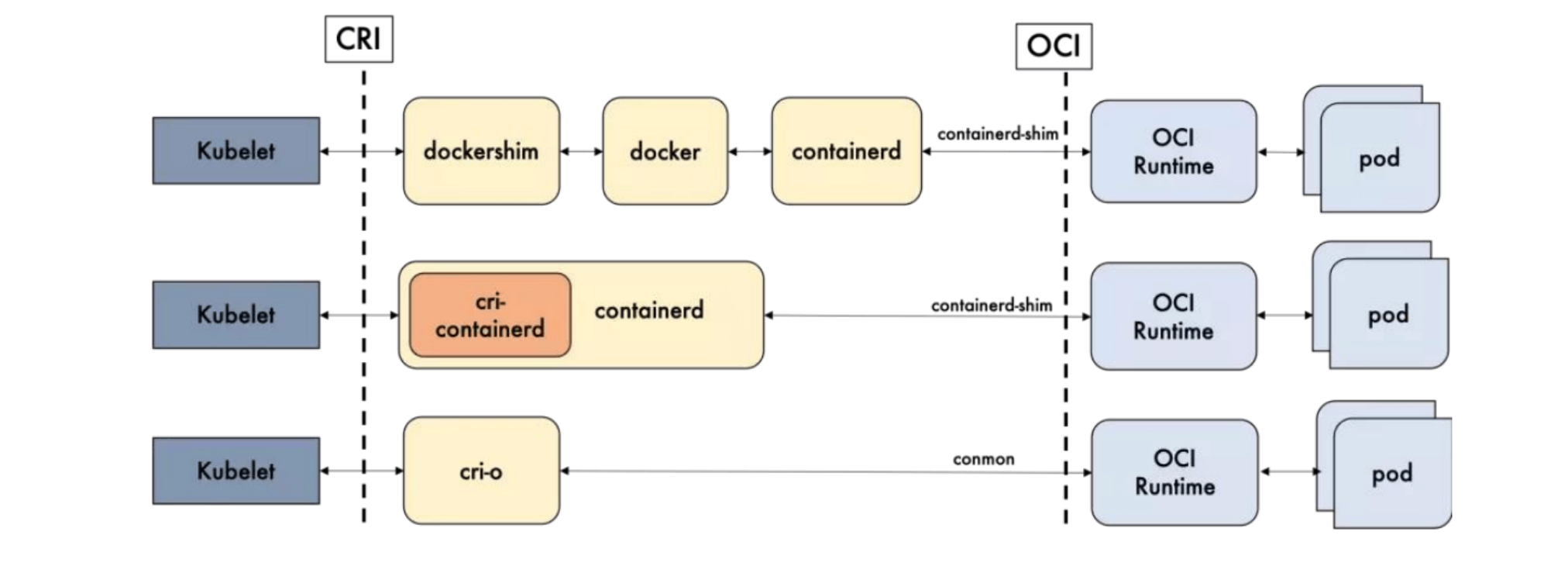

Dockershim, containerd, and CRI-O are all container runtimes that follow CRI, which we call high-level runtimes.

OCI defines the open source industry standards for creating container formats and runtime, including Image Specification and runtime specification.

Image Specification defines the OCI image standard. High-level runtimes will download an OCI image and extract it into an OCI runtime file system bundle.

Runtime Specification describes how to run container programs from OCI runtime file system bundle and defines its configuration, runtime environment, and lifecycle. Operations such as setting namespaces and control groups (cgroups) for new containers and mounting root file systems (rootfs) are all defined here. Its reference implementation is runc, which we call Low-level Runtime.

- High-level Runtime: Mainly includes Docker, containerd, and CRI-O

- Low-level Runtime: Includes runc, kata, and gVisor.

Low-level runtimes kata and gVisor are still in small-scale deployment or experimental stages, with relatively lacking ecosystem maturity and use cases. So unless there are special requirements, runc is almost the inevitable choice. Therefore, when choosing container runtimes, the focus is mainly on the selection of high-level runtimes.

You might still not understand. Simply put, one side connects to Kubernetes, the other side connects to container processes. The former is high-level runtime, the latter is low-level runtime.

OCI

OCI (Open Container Initiative) defines the open source industry standards for creating container formats and runtime, including:

- Image Specification: Defines the OCI image standard. High-level runtimes will download an OCI image and extract it into an OCI runtime file system bundle (filesystem bundle).

- Runtime Specification: Describes how to run container programs from OCI runtime file system bundle and defines its configuration, runtime environment, and lifecycle, such as how to set namespaces and control groups (cgroups) for new containers and mount root file systems.

CRI Method List

Comparison of Open Source Runtimes

Docker’s multi-layer encapsulation and calls lead to slightly inferior maintainability, increasing the difficulty of troubleshooting online problems. Almost except for restarting Docker, we have no other options. The solutions of containerd and CRI-O are much simpler than Docker.

Docker can be understood as a superset of containerd. If you use docker as runtime, it’s equivalent to starting a heavy dockershim.

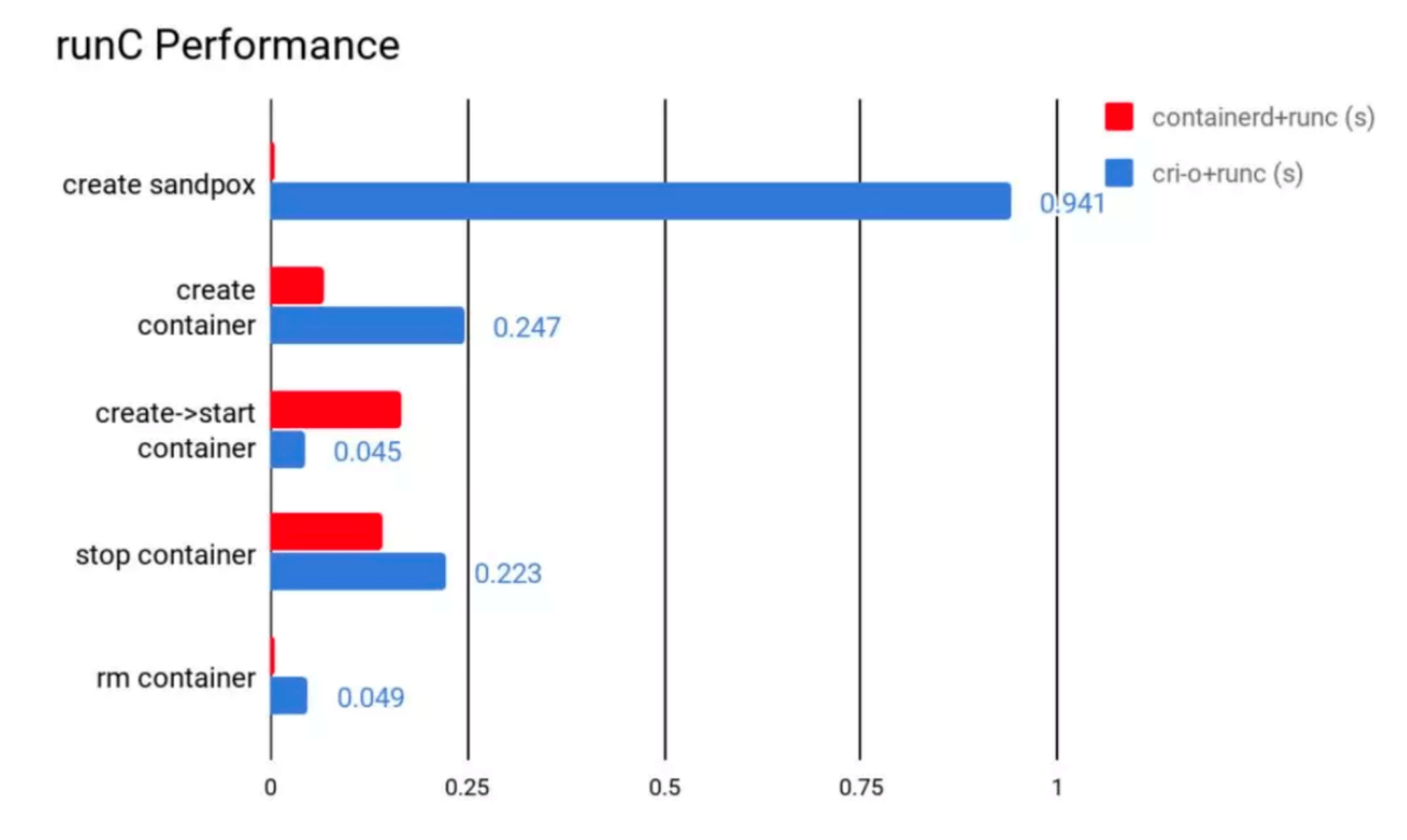

Performance Differences

containerd performs well in all aspects except for container startup. From the total time perspective, containerd’s time consumption is still shorter than CRI-O.

So ultimately containerd wins as the optimal solution, though cri-o + runc is also acceptable.

Pros and Cons Comparison

In terms of functionality, both containerd and CRI-O comply with CRI and OCI standards; in terms of stability, containerd has a slight advantage; in terms of performance, containerd wins.

| containerd | CRI-O | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Better | Good | |

| Features | Good | Good | CRI & OCI Compatible |

| Stability | Stable | Unknown |

Docker & Containerd

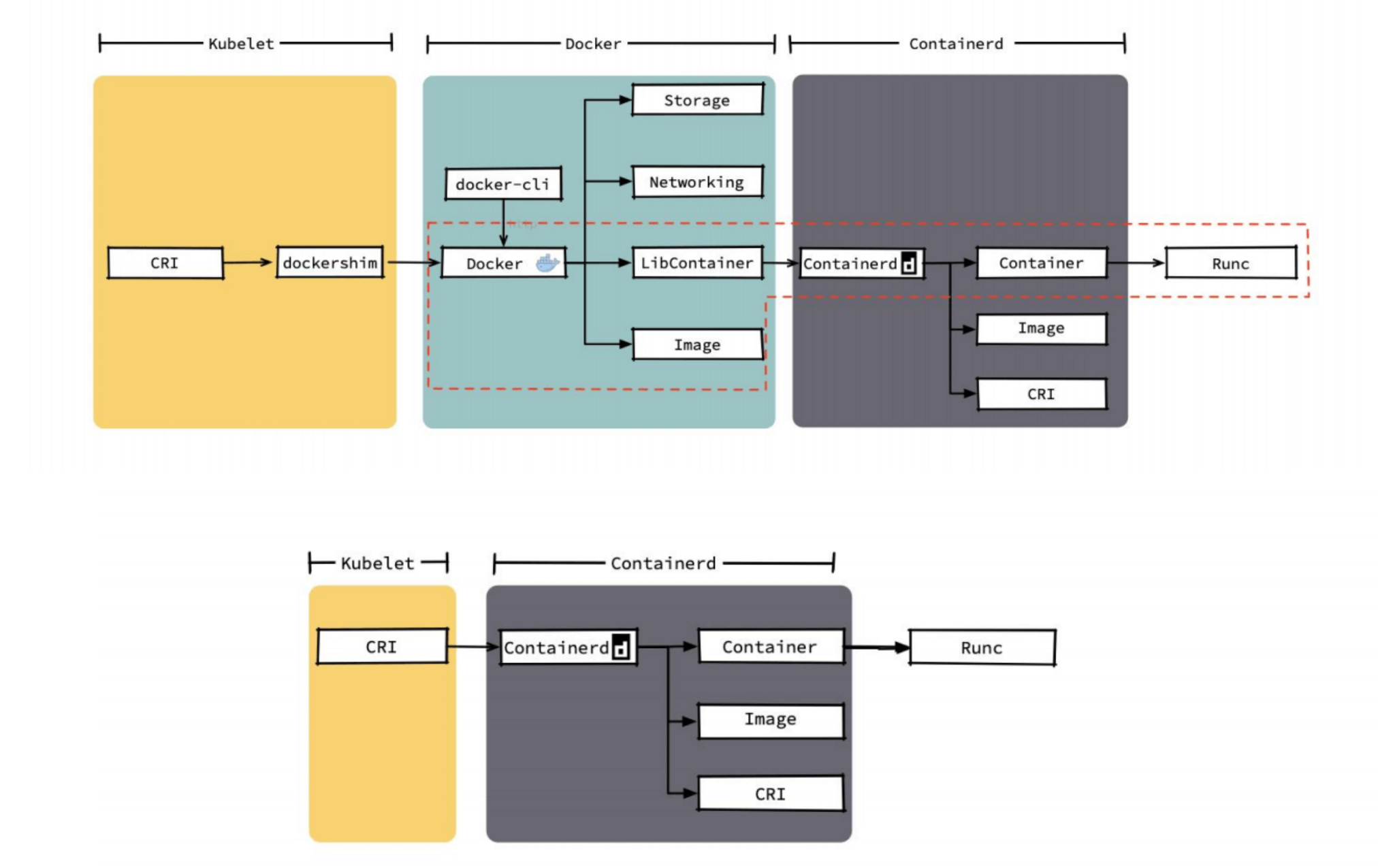

The core component for container runtime functionality inside Docker is containerd. Later, containerd can also directly interface with kubelet through CRI and be used independently in Kubernetes.

This is quite subtle. containerd also provides CLI tools:

crictl pods # can also read pod information

Compared to Docker, containerd reduces the processing modules Dockerd and Docker-shim required by Docker and optimizes the storage drivers supported by Docker. Therefore, it has performance advantages in container creation, startup, stopping, and deletion, as well as in image pulling. The simplified architecture also brings maintenance convenience.

Of course, Docker also has many features that containerd doesn’t have, such as supporting zfs storage drivers, supporting size and file limits for logs, and in the case of using overlayfs2 as storage driver, it can limit the size of container writable layers through xfs_quota. Despite this, containerd can currently basically meet various container management needs, so more and more systems are using it as runtime.

Detailed Differences between docker and containerd

You can see that docker has many features that k8s doesn’t need. k8s only needs the parts in the red box; the rest are redundant. Even if we remove these parts, the remaining call chain is still very long.

In comparison, containerd’s entire code and call chain are far superior to docker’s.

How to Switch from Docker to Containerd

https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/production-environment/container-runtimes/#containerd

Stop service

systemctl stop kubelet

systemctl stop docker

systemctl stop containerd

Create containerd config folder:

Configure containerd:

sudo mkdir -p /etc/containerd

containerd config default | sudo tee /etc/containerd/config.toml

In containerd, the

sandbox_imageparameter:❯ containerd config default | sudo tee /etc/containerd/config.toml | grep -i "sandbox_image" sandbox_image = "k8s.gcr.io/pause:3.1"Cannot be downloaded in China without VPN.

Update default config

sed -i s#k8s.gcr.io/pause:3.5#registry.aliyuncs.com/google_containers/pause:3.5#g /etc/containerd/config.toml

sed -i s#'SystemdCgroup = false'#'SystemdCgroup = true'#g /etc/containerd/config.toml

Can configure image mirror to Aliyun Cloud

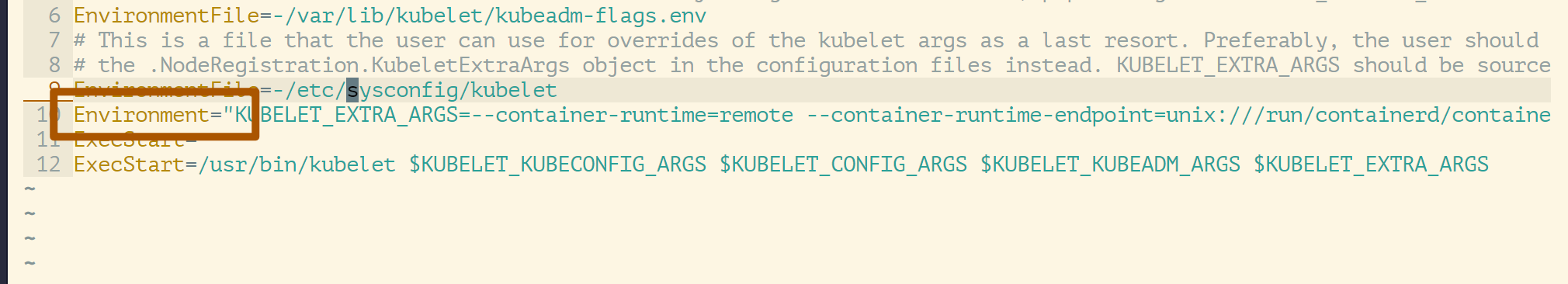

Edit kubelet config and add extra args

vim /etc/systemd/system/kubelet.service.d/10-kubeadm.conf

Environment="KUBELET_EXTRA_ARGS=--container-runtime=remote --container-runtime-endpoint=unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock --pod-infra-container-image=registry.aliyuncs.com/google_containers/pause:3.5"

Next is to modify Kubernetes startup parameters, telling Kubernetes that my runtime should be changed to containerd.

This location is where kubelet gRPC calls.

Restart

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart containerd

systemctl restart kubelet

Config crictl to set correct endpoint

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock

EOF

CNI

Kubernetes Cluster Networking

OK, I think Kubernetes cluster networking is very complex, and networking itself is very complex. This is true even for engineers with virtual networking and request routing operations experience. Many books (including docker and Kubernetes tutorials) approach network learning as a gradual process. Kubernetes starts from docker networking, docker starts from Linux. We also understood some core networking concepts in the previous docker section, so let’s start from Linux networking.

Linux namespaces contain some fundamental technologies behind most modern container implementations. At a high level, they allow isolation of global system resources between independent processes. For example, PID namespaces isolate the process ID number space. This means that two processes running on the same host can have the same PID!

This level of isolation is obviously useful in the container world. For example, without namespaces, a process running in container A might unmount an important file system in container B, or change the hostname of container C, or delete a network interface from container D. By namespacing these resources, processes in container A don’t even know that processes in containers B, C, and D exist.

The fundamental principles of Kubernetes network model design are:

- All Pods can access each other without NAT.

- All nodes can access each other without NAT.

- The IP address that containers see inside and the container IP that external components see are the same.

In Kubernetes clusters, IP addresses are allocated on a per-Pod basis, and each Pod has an independent IP address. All containers within a Pod share a network stack, i.e., a network namespace on the host machine, including their IP addresses, network devices, configurations, etc. This means that all containers in a Pod can connect to each other through localhost:port.

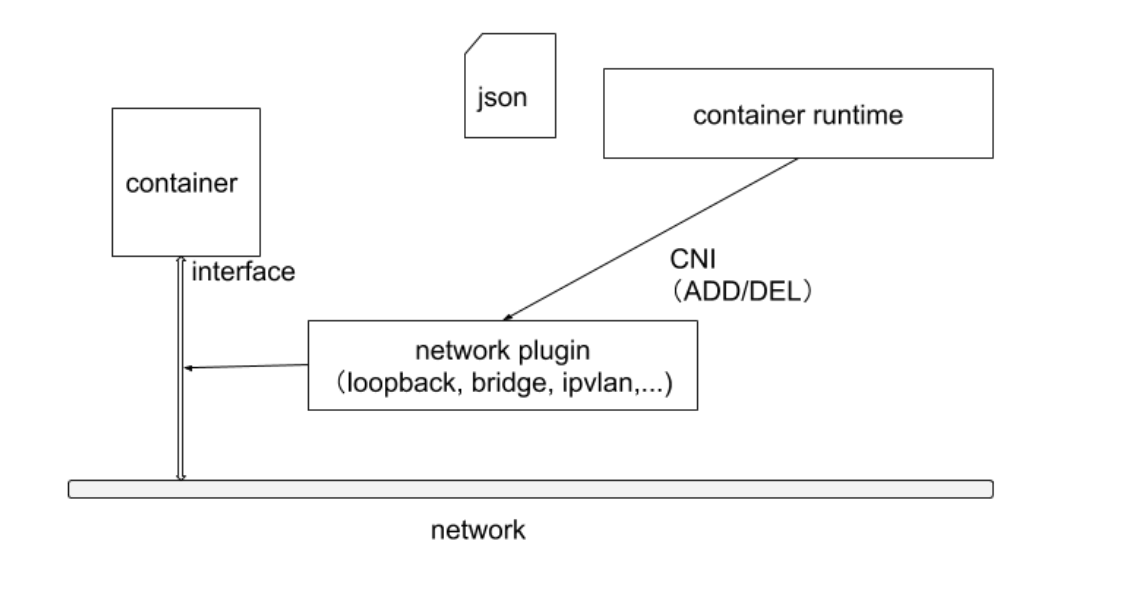

In Kubernetes, a lightweight universal container network interface CNI (Container Network Interface) is provided specifically for setting up and tearing down container network connectivity. Container runtimes complete container network setup by calling network plugins through CNI.

CNI Plugin Classification and Common Plugins

- IPAM: IP address allocation

- Main plugin: Network interface setup

bridge: Create a bridge and insert host and container ports into the bridgeipvlan: Addipvlaninterface for containersloopback: Set uploopbackinterface

- Meta: Additional functionality

portmap: Set up host port and container port mappingbandwidth: UseLinux Traffic Controlfor rate limitingfirewall: Set up firewall rules for containers throughiptablesorfirewalld

https://github.com/containernetworking/plugins

CNI Plugin Runtime Mechanism

Container runtimes read JSON format configuration files from CNI’s configuration directory at startup.

cat /etc/cni/net.d # Read this CNI configuration file

ls -al /opt/cni/bin # CNI executable binary files

Files with extensions .conf, .conflist, .json. If the configuration directory contains multiple files, generally, the first configuration file in alphabetical order is selected as the default network configuration, and the specified CNI plugin name and configuration parameters are loaded from it.

We can see there’s a file ending with

.conflist. Yes, k8s CNI allows using multiple plugins simultaneously and passes the execution result of the previous plugin as parameters to the next plugin, so we can chain multiple plugins to let multiple plugins do different things. For example, the first plugin can only be responsible for communication between nodes on the same host, then the second plugin can be responsible for communication between pods on different nodes. In short, as I said, configuration files are available, pod information is also passed by k8s, how you want to play is up to your plugin~

For container network management, container runtimes generally need to configure two parameters --cni-bin-dir and --cni-conf-dir.

cni-bin-dir: Directory where network plugin executable files are located. Default is/opt/cni/bin.cni-conf-dir: Directory where network plugin configuration files are located. Default is/etc/cni/net.d.

There’s a special case where kubelet’s built-in Docker as container runtime, kubelet looks for CNI plugins and runs plugins to set up networking for containers. These two parameters should be configured at kubelet.

After k8s v1.24 completely removes docker, this special case won’t need to be considered.

The specific process is as follows:

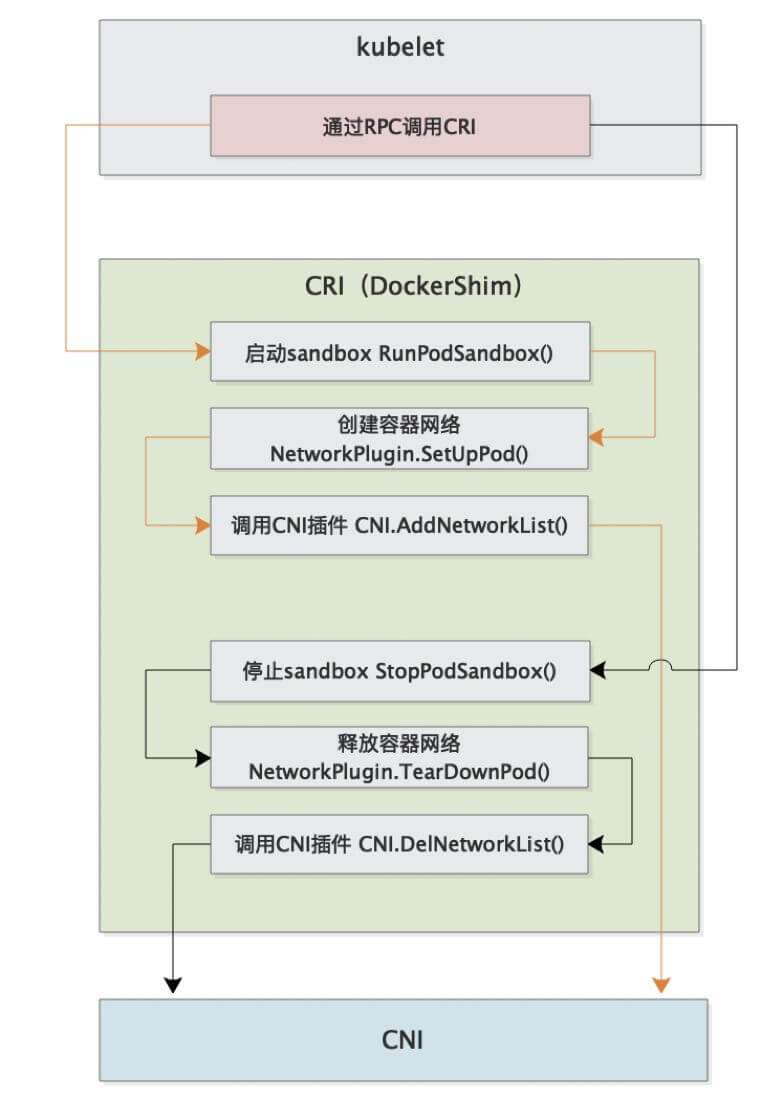

The complete call chain is as follows:

First, Pod is started by kubelet, then kubelet starts Pod through CRI interface.

The process of starting Pod includes network-related configuration, which needs to be implemented by CRI calling CNI.

Therefore, the entire call chain is kubelet --> CRI --> CNI.

CNI Deployment?

When CNI plugins are deployed, they usually start a DaemonSet and copy binary files from the image to the host’s /opt/cni/bin directory, completing the deployment.

Therefore, writing a CNI plugin actually means providing some binary files with corresponding functionality for kubelet to call.

CNI can set multiple plugins, but CNI is executed in order~

CNI Plugin Design Considerations

- Container runtime must create a new network namespace for containers before calling any plugins.

- Container runtime must determine which networks this container belongs to and which plugins must be executed for each network.

- Container runtime must load configuration files and determine which plugins must be executed when setting up networks

- Network configuration uses

JSONformat and can be easily stored in files. - Container runtime must execute corresponding plugins in configuration files in order

- After completing container lifecycle, container runtime must execute plugins in reverse order of adding containers to disconnect containers from networks

- Container runtime cannot perform parallel operations when called by the same container but allows parallel operations when called by different containers.

- Container runtime must execute ADD and DEL operations in order for a container. ADD is always followed by corresponding DEL. DEL may be followed by additional DELs, and plugins should allow handling multiple DELs.

- Containers must be uniquely identified by

ContainerID. Plugins that need to store state should use a primary key composed of network name, container ID, and network interface for indexing. - Container runtime cannot call ADD command twice consecutively for the same network, same container, same network interface.

Bridging Host Layer Networks

Besides CNI plugins, Kubernetes also requires standard CNI plugin lo with minimum version 0.2.0. Network plugins, besides supporting setting up and cleaning Pod network interfaces, also need to support Iptables. If Kube-proxy works in Iptables mode, network plugins need to ensure container traffic can use Iptables forwarding. For example, if network plugins connect containers to Linux bridge, the net/bridge/bridge-nf-call-iptables sysctl parameter must be set to 1, so packets on the bridge will traverse Iptables rules. If plugins don’t use Linux bridge (but use something like Open vSwitch or other mechanisms), they should ensure container traffic is properly routed.

CNI Plugin

The ContainerNetworking group maintains some CNI plugins, including bridge, ipvlan, loopback, macvlan, ptp, host-device for network interface creation, DHCP, host-local and static for IP address allocation, and others like Flannel, tuning, portmap, firewall. The community also has some third-party network policy plugins, such as Calico, Cilium, and Weave. The diversity of available options means most users will be able to find CNI plugins suitable for their current needs and deployment environment and quickly switch solutions when circumstances change.

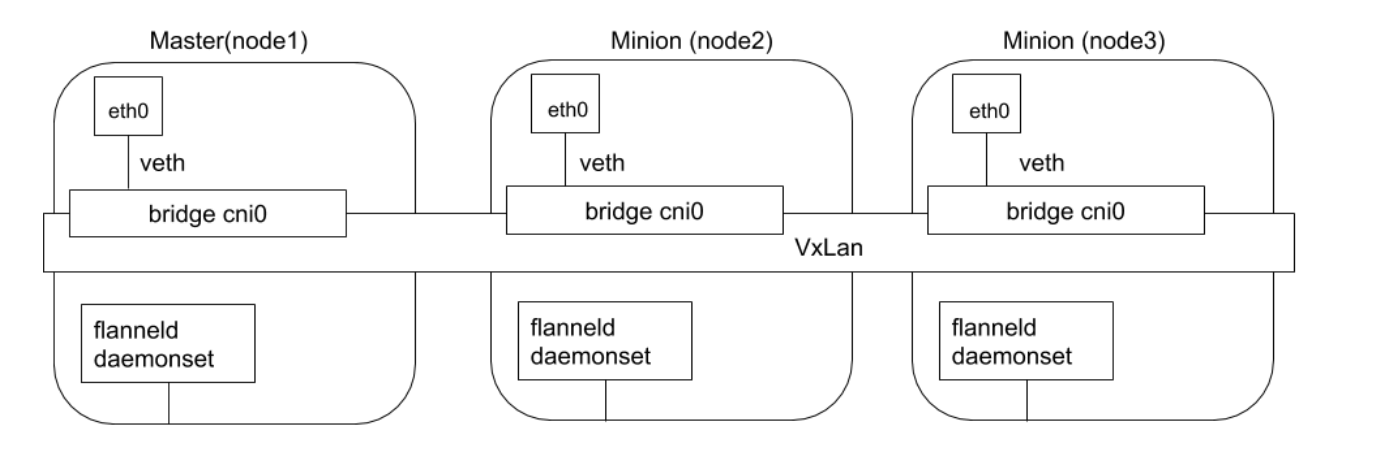

Flannel

Flannel is a project developed by CoreOS, an early entry-level CNI plugin product that’s simple and easy to use. Flannel uses the existing etcd cluster of Kubernetes cluster to store its state information, eliminating the need for dedicated data storage. It only needs to run the flanneld daemon on each node.

Each node is assigned a subnet for allocating IP addresses to Pods on that node. Pods on the same host can communicate using bridges, while Pods on different hosts will have their traffic encapsulated in UDP packets by flanneld and routed to appropriate destinations. The default and recommended encapsulation method is VxLAN because it has good performance and requires less manual intervention than other options. While encapsulation solutions using technologies like VxLAN work well, the downside is that this process makes traffic tracing difficult.

Meanwhile, Flannel doesn’t support network policy.

Flannel implements through packet encapsulation and decapsulation.

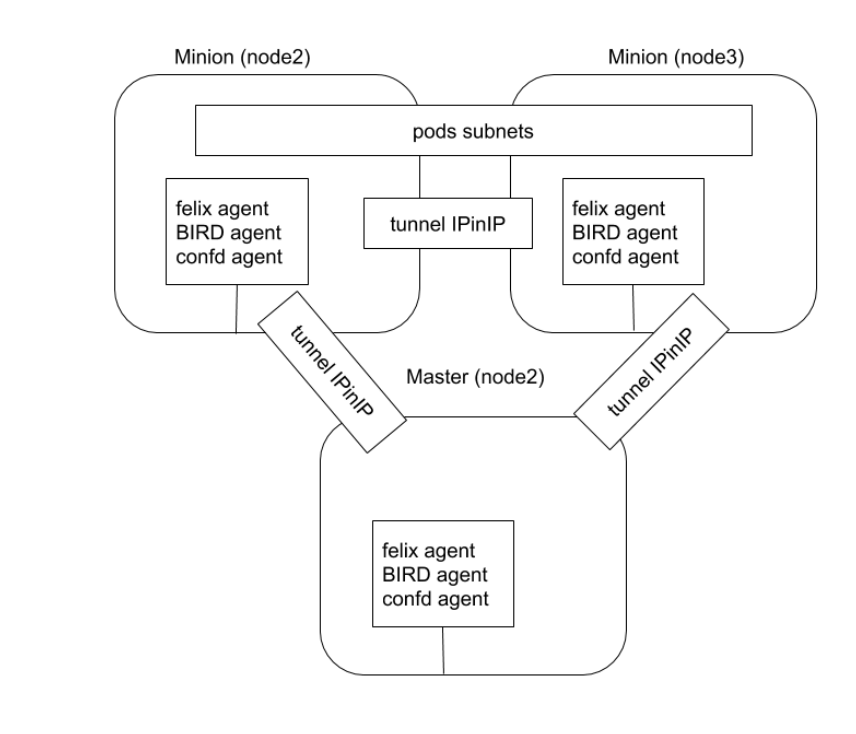

Calico

Calico is known for its performance, flexibility, and network policies, involving not only providing network connectivity between hosts and Pods but also network security and policy management.

For same-segment communication, based on Layer 3, Calico uses BGP routing protocol to route packets between hosts. Using BGP routing protocol also means packets don’t need to be wrapped in additional encapsulation layers when moving between hosts.

For cross-segment communication, based on IPinIP using virtual network device tunl0, one IP packet encapsulates another IP packet. The source address of the outer IP packet header is the IP address of the tunnel entrance device, and the destination address is the IP address of the tunnel exit device.

Network policy is one of Calico’s most popular features, using ACLS protocol and kube-proxy to create iptables filtering rules to achieve container network isolation.

Additionally, Calico can integrate with service mesh Istio to interpret and enforce cluster workload policies at both service mesh layer and network infrastructure layer. This means powerful rules can be configured to describe how Pods should send and receive traffic, improving security and strengthening control over network environments.

Calico belongs to a completely distributed horizontal scaling architecture, allowing developers and administrators to quickly and smoothly scale deployment. For environments with high performance and functionality requirements (like network policies), Calico is a good choice.

Calico has two modes:

- Packet encapsulation/decapsulation tunnel mode

- Dynamic routing mode

Calico Runtime Process

After plugin deployment, it starts DaemonSet, which mounts directories containing configuration files (/etc/cni/net.d) and binary files (/opt/cni/bin) to the Pod, then copies configuration files and binary files from the image to corresponding directories.

DaemonSet runs on all nodes, so it can handle node additions or deletions.

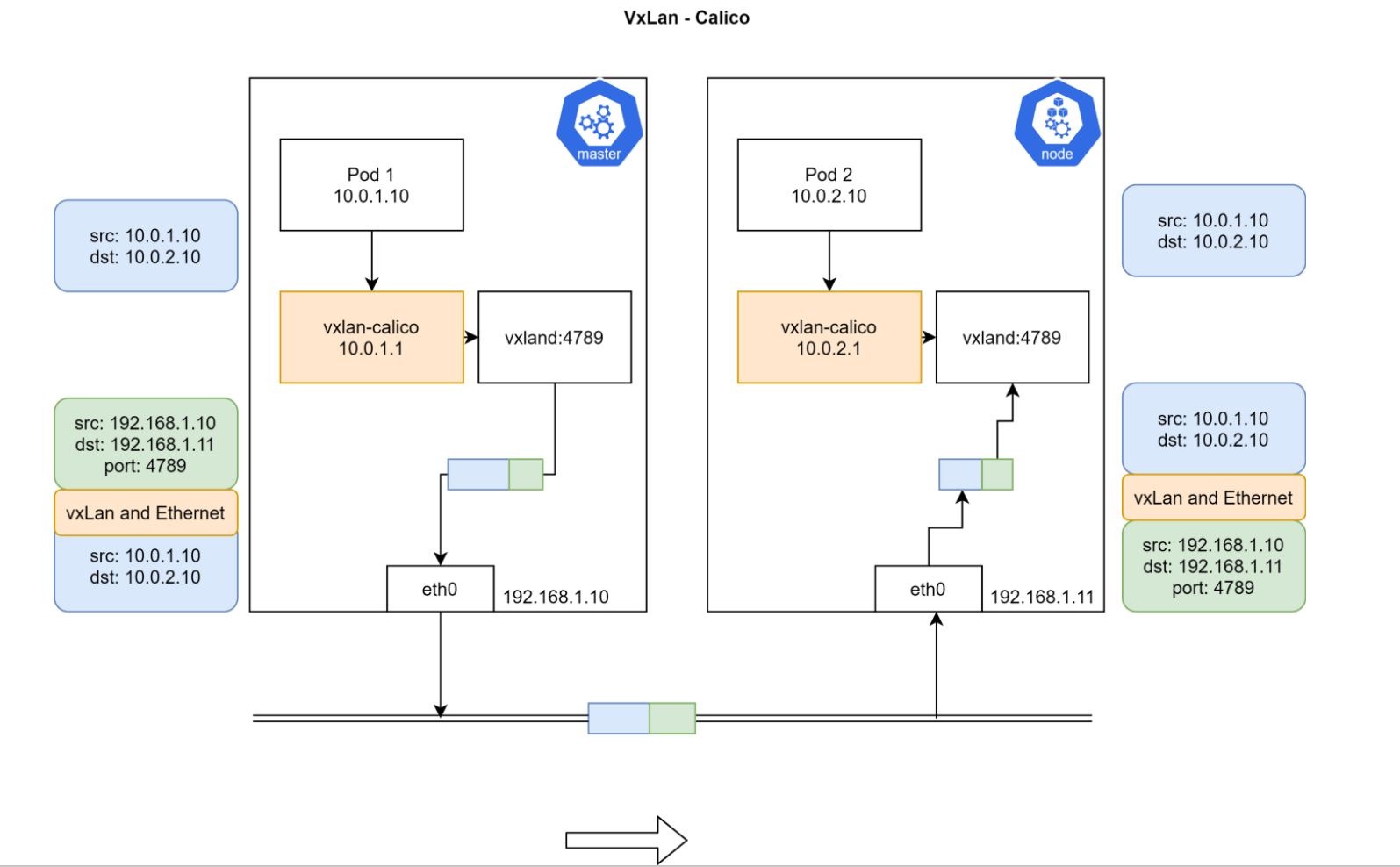

Calico VxLAN

Pod1 and Pod2 are on different Nodes and don’t belong to the same network segment, so they cannot be directly routed.

After installing Calico, there will be a vxland process and vxlan-calico network device on each node. Data from Pod goes through vxlan-calico device to vxland process, which performs packet encapsulation, taking the entire network packet from Pod as payload, then adding IP headers again. The source IP added here is the current node’s IP + vxland listening port 4789, and the destination IP is the IP of the Node where Pod2 is located. Then this packet goes through external node routing from master node to node, then node’s vxland performs packet decapsulation and enters Pod2 through vxlan-calico device.

Actually the principle is the same as Flannel, both use packet encapsulation/decapsulation

IPAM Data Storage

Calico uses CRD creation in clusters for storage by default.

Other storage methods can also be configured

- IPPool: Defines a cluster’s predefined IP range

- IPAMBlock: Defines pre-allocated IP range for each host

- IPAMHandle: Records specific details of IP allocation

Calico Data Flow Demonstration

Different Pods on Same Node

First start a container containing many tools, like centos

kubectl run --image=centos centos

Then enter that Pod

$ k exec -it centos-5fdd4bb694-7cgc8 bash

Check that Pod’s IP and routing information

$ ip a

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

3: eth0@if48: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1450 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

link/ether 16:4c:ec:e4:3a:d6 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 192.168.119.78/32 brd 192.168.119.78 scope global eth0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

$ ip r

default via 169.254.1.1 dev eth0

169.254.1.1 dev eth0 scope link

You can see there’s a default route where all data must be sent to 169.254.1.1 through eth0.

Then use arpping to see which device 169.254.1.1 IP corresponds to

$ arping 169.254.1.1

ARPING 169.254.1.1 from 192.168.119.78 eth0

Unicast reply from 169.254.1.1 [EE:EE:EE:EE:EE:EE] 0.579ms

Unicast reply from 169.254.1.1 [EE:EE:EE:EE:EE:EE] 0.536ms

Found this IP corresponds to MAC address EE:EE:EE:EE:EE:EE.

Then exit container and check on host if there are devices with all-e MAC addresses

$ ip a

45: calie3f1daf7d15@if3: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1450 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

link/ether ee:ee:ee:ee:ee:ee brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 11

inet6 fe80::ecee:eeff:feee:eeee/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Found there really are devices starting with cali that all have this MAC address. These are actually veth pairs created by calico, with one end in Pod and one end on host.

Then check routing information on host

[root@agent-1 ~]# ip r

default via 192.168.10.1 dev eth0

169.254.169.254 via 192.168.10.3 dev eth0 proto static

blackhole 172.25.0.128/26 proto 80

172.25.0.131 dev cali1cc9705ed50 scope link

172.25.0.132 dev cali9d0f51d41f9 scope link

172.25.0.133 dev cali4dcdb8d77a9 scope link

172.25.0.134 dev caliac318995356 scope link

Found that traffic for several IPs needs to be forwarded to cali* devices. Actually this traffic goes through veth pairs into other containers, which is why pinging other Pods from within Pod works.

Traffic goes to host, makes a round trip, and enters Pod again.

Pods on Different Nodes

Specific node and IP information as follows:

ipamblock:

10-233-90-0-24

node1

cidr: 10.233.90.0/24

ipamblock:

10-233-96-0-24

node: node2

cidr: 10.233.96.0/24

After calico deployment, it starts a daemon process called bird, whose function is to synchronize routing information between different nodes.

Pod networks are actually private information with no relation to host networks. Other nodes cannot perceive Pod network segments on current node, so bird tool is needed for synchronization.

The specific information synchronized is the binding relationship between IP segments and host IPs. For example, to access IP segment 10.233.96.0/24, forward to 192.168.34.11; to access IP segment 10.233.90.0/24, forward to 192.168.34.10.

Therefore, node1 will have routing information pointing to node2:

10.233.96.0/24 via 192.168.34.11 dev tunl0 proto bird onlink

Similarly, node2 also has routing information to node1:

10.233.90.0/24 via 192.168.34.10 dev tunl0 proto bird onlink

This way they can communicate with each other.

Specific bird-related information can be viewed through calico daemonset:

$ k get po -n calico-system calico-node-xk4kn -oyaml

- name: CALICO_NETWORKING_BACKEND

value: bird

name: calico-node

readinessProbe:

exec:

command:

- /bin/calico-node

- -bird-ready

- -felix-ready

failureThreshold: 3

periodSeconds: 10

successThreshold: 1

timeoutSeconds: 5

Check bird process on host

$ ps -ef|grep bird

root 2433 2386 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 runsv bird

root 2435 2386 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 runsv bird6

root 2505 2469 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 svlogd -ttt /var/log/calico/bird6

root 2516 2510 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 svlogd -ttt /var/log/calico/bird

root 3662 2433 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 bird -R -s /var/run/calico/bird.ctl -d -c /etc/calico/confd/config/bird.cfg

root 3664 2435 0 10:58 ? 00:00:00 bird6 -R -s /var/run/calico/bird6.ctl -d -c /etc/calico/confd/config/bird6.cfg

root 9167 5788 0 11:05 pts/0 00:00:00 grep --color=auto bird

Enter Pod to check bird configuration file

$ k exec -it calico-node-7hmbt -n calico-system cat /etc/calico/confd/config/bird.cfg

router id 192.168.34.2;

protocol direct {

debug { states };

interface -"cali*", -"kube-ipvs*", "*"; # Exclude cali* and kube-ipvs* but

# include everything else. In

# IPVS-mode, kube-proxy creates a

# kube-ipvs0 interface. We exclude

# kube-ipvs0 because this interface

# gets an address for every in use

# cluster IP. We use static routes

# for when we legitimately want to

# export cluster IPs.

}

Corresponding iptables rules:

iptables-save, masq all traffic to outside

-A cali-nat-outgoing -m comment --comment "cali:flqWnvo8yq4ULQLa" -m set --match-set cali40masq-ipam-pools src -m set ! --match-set cali40all-ipam-pools dst -j MASQUERADE --random-fully

CNI Plugin Comparison

For production, generally consider calico or Cilium. Flannel is no longer maintained.

| Solution | Network Policy Support | IPv6 Support | Network Layer Base | Deployment | CLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calico | Yes | Yes | L3(IPinIP,BGP) | DaemonSet | calicoctl |

| Cilium | Yes | Yes | L3 / L4+L7(filtering) | DaemonSet | cilium |

| Contiv | No | Yes | L2(VxLAN) / L3(BGP) | DaemonSet | None |

| Flannel | No | No | L2(VxLAN) | DaemonSet | None |

| Weave net | Yes | Yes | L2(VxLAN) | DaemonSet | None |

References

【K8s Concepts】Understanding Container Network Interface CNI and CNI Plugins

【Dry Goods Sharing】Kubernetes Container Network CNI Discussion

K8s Networking: Deep Understanding of CNI

CSI

Kubernetes CSI (Container Storage Interface) is a storage interface designed for containerized environments, used to integrate persistent storage systems into Kubernetes clusters. The purpose of this interface is to improve storage system pluggability and portability while simplifying storage system management.

Kubernetes supports implementing support and extension for different storage through plugins, based on three approaches:

- FlexVolume

- in-tree volume plugins

- CSI

Among these, CSI is a standardized storage interface that allows Kubernetes to interact with various storage backends. CSI improves storage system pluggability and portability and simplifies storage system management. By understanding how CSI works and how to use it, you can better utilize storage functionality provided by Kubernetes.

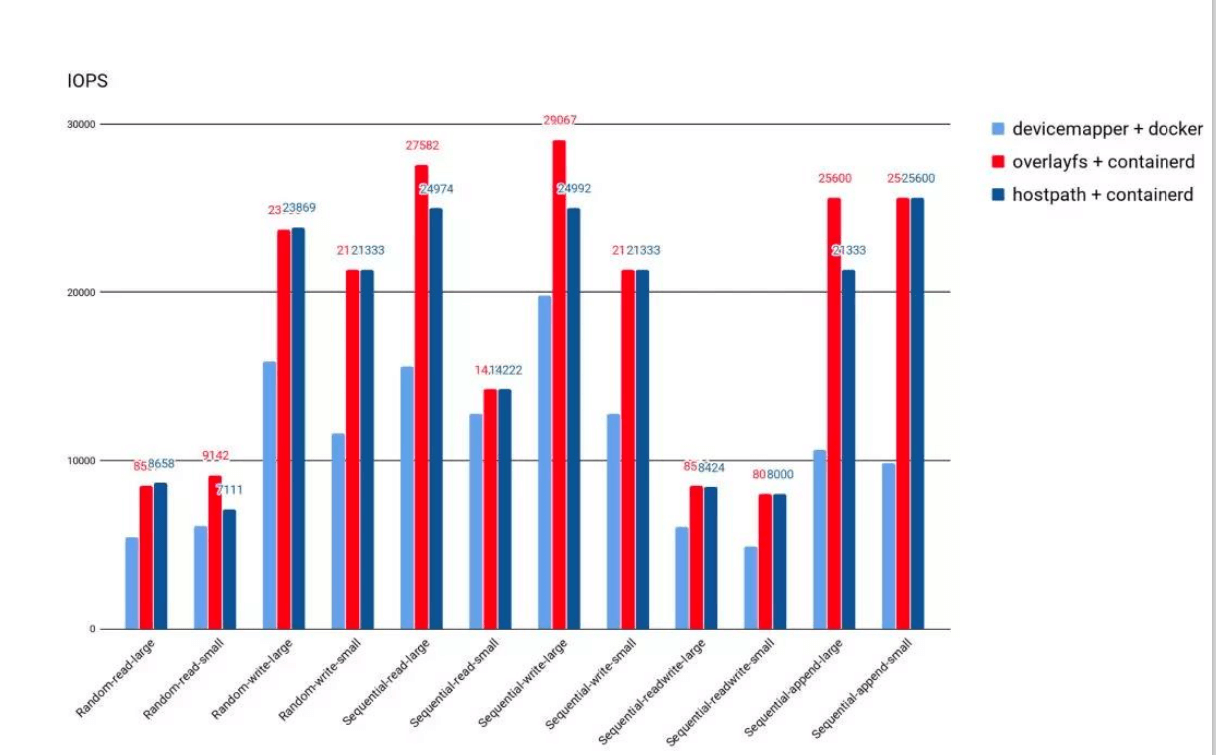

Container Runtime Storage

- Besides external storage volumes, after container startup, the performance of runtime file systems directly affects container performance;

- Early Docker used Device Mapper as container runtime storage driver because OverlayFS hadn’t been merged into Kernel yet;

- Currently, both Docker and containerd default to

OverlayFSas runtime storage driver; - OverlayFS currently has very good performance, 20% better than DeviceMapper, almost identical to host file operation performance.

Note this is runtime storage, a file system used for pulling runtime only. It’s not recommended to write anything or logs, as this will affect efficiency.

Storage Volume Plugin Management

Kubernetes supports implementing support and extension for different storage through plugins, based on three approaches:

in-treeplugins: Directly download plugins from k8s repository. Currently, k8s community no longer accepts newin-treestorage plugins; they must be supported as out-of-tree pluginsout-of-tree FlexVolumeplugins: This mode is also gradually being phased outFlexVolumemeans Kubernetes interacts with storage plugins by calling local executable files on compute nodesFlexVolumeplugins require host root privileges to install plugin driversFlexVolumestorage drivers require hosts to install tools like attach and mount, also needing root access permissions.

out-of-tree CSIplugins: CSI plugins interact with storage drivers through RPC, currently mainstream plugin format.

Thinking: Can CNI plugins also be changed to this calling method?

Kubernetes CSI is a storage interface specifically designed for containerized environments that allows Kubernetes to interact with various storage backends. CNI plugins (Container Network Interface) are also Kubernetes plugins, but they have different functions and roles from CSI. CNI plugins are used to integrate network plugins into Kubernetes to provide network services for containers, while CSI plugins are used to integrate persistent storage systems into Kubernetes clusters to provide persistent storage services for containers. Although both CNI and CSI plugins are plugin mechanisms, their calling methods and implementation approaches are different, so CNI plugins cannot be changed to CSI plugin calling methods.

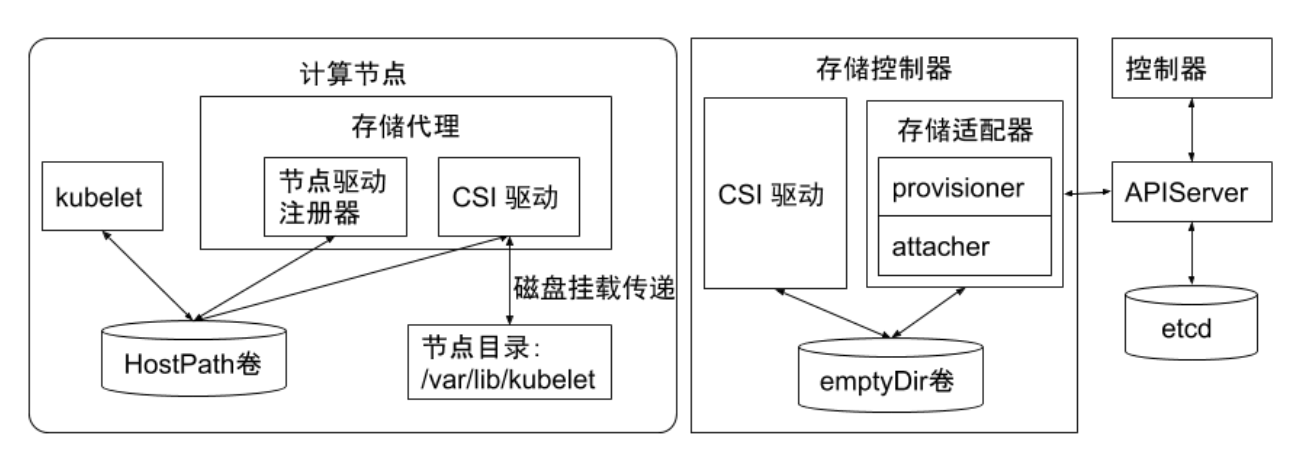

CSI Plugins

CSI drivers are bridges between CSI interfaces and storage backends. They allow Kubernetes to interact with various storage backends (such as local storage, network storage, cloud storage) and can be loaded and unloaded as plugins.

The Kubernetes community has written CSI drivers for some storage backends (such as Ceph, NFS, and AWS EBS) and supports other storage backends in writing their own CSI drivers. These drivers allow Kubernetes to interact with storage backends and expose storage backend functionality to Kubernetes users.

When designing CSI, Kubernetes has few requirements for CSI storage driver packaging and deployment, mainly defining two related Kubernetes modules:

- kube-controller-manager :

- kube-controller-manager module is used to sense CSI driver existence.

- Kubernetes master modules interact directly through Unix domain socket (rather than CSI drivers) or other methods.

- Kubernetes master modules only interact with Kubernetes-related APIs, so if CSI drivers have operations dependent on Kubernetes API, such as volume creation, volume attach, volume snapshots, etc., they need to trigger related CSI operations through Kubernetes API in CSI drivers.

- kubelet:

- kubelet module is used to interact with CSI drivers.

- kubelet initiates CSI calls (like NodeStageVolume, NodePublishVolume, etc.) to CSI drivers through Unix domain socket, then initiates mount and unmount volumes.

- kubelet discovers CSI drivers and Unix Domain Sockets for interacting with CSI drivers through plugin registration mechanism.

- All CSI drivers deployed in Kubernetes clusters must register themselves through kubelet’s plugin registration mechanism.

Using CSI plugins:

To use CSI, the following steps need to be completed:

- Install CSI drivers: CSI drivers can be obtained from storage backend vendors or Kubernetes community and installed in Kubernetes clusters. The installation process includes placing CSI driver binary files in correct locations, creating CSI driver DaemonSet and ConfigMap, etc.

- Create StorageClass: StorageClass defines how to allocate storage for dynamic volumes. StorageClass can be created using kubectl commands or YAML files. When creating StorageClass, parameters like storage backend, storage type, volume size need to be specified.

- Create PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC): PVC is a declaration requesting container volumes. PVC can be created using kubectl commands or YAML files. When creating PVC, parameters like StorageClass, volume size, access modes need to be specified.

- Use PVC: PVC can be attached to Pods and referenced within them. When defining Pods, PVC names need to be specified as part of volumeMounts and volumes fields.

CSI Drivers

CSI drivers generally include modules like external-attacher, external-provisioner, external-resizer, external-snapshotter, node-driver-register, CSI driver, which can be deployed in different ways according to actual storage types and requirements.

| Module | Description |

|---|---|

| external-attacher | Used to attach existing storage volumes to nodes |

| external-provisioner | Used to create new storage volumes on storage backend and attach them to nodes |

| external-resizer | Used to resize storage volumes |

| external-snapshotter | Used to create snapshots for storage volumes and restore them when needed |

| node-driver-register | Used to register CSI drivers to Kubernetes nodes |

| CSI driver | Used to implement CSI interface and interact with storage backend |

hostPath volume is the simplest and most common volume type in Kubernetes, which can mount directories or files on nodes to containers. hostPath volumes are very suitable for temporary storage, such as log files. However, since hostPath volume lifecycle is closely related to Pod lifecycle, it’s not suitable for persistent storage. If Pod is deleted, data in hostPath volume won’t be cleaned and will remain there.

emptyDir volume is another simple volume type in Kubernetes, which is an empty directory created when Pod is created. emptyDir volumes can be used to share files between containers and also for storing temporary data like log files. Unlike hostPath volumes, emptyDir volume lifecycle is the same as Pod lifecycle. When Pod is deleted, data in emptyDir volume is also deleted.

- Semi-persistent storage volumes (EmptyDir): Data volumes storing temporary data within Pod lifecycle, used for sharing data between containers, but data is cleared when Pod restarts.

- Temporary storage volumes: Storage volumes deleted when Pod lifecycle ends, usually used for storing temporary data like log files. These volumes don’t need manual cleanup because they’re automatically cleaned when Pods are deleted.

- Persistent storage volumes: Storage volumes that can be shared between Pods and retain data even when Pods restart or reschedule. Kubernetes supports various types of persistent storage volumes like NFS, iSCSI, HostPath, AWS EBS, etc.

Besides these three storage volume types, Kubernetes storage functionality can be extended by defining custom storage volumes. Custom storage volumes can be implemented through Kubernetes plugins or external storage systems.

When using storage volumes, one or more volumes need to be defined in Pod’s YAML configuration file, then volumeMounts are used in containers to mount these volumes. This way, containers can access data stored in volumes.

If persistent storage volumes need to be used for data storage, storage classes also need to be set up in Kubernetes clusters. Storage classes are Kubernetes resources used to define storage volume types, which can map PVCs to specific storage volume types and providers.

Temporary Storage Volumes

Common temporary storage is mainly emptyDir volumes.

emptyDir is a volume type frequently used by users. As the name suggests, the “volume” is initially empty. When Pod is removed from node, data in emptyDir volume is also permanently deleted. But when Pod containers exit and restart for some reason, data in emptyDir volume won’t be lost.

By default, emptyDir volumes are stored on storage media supporting that node, which can be local disk or network storage. emptyDir can also notify Kubernetes to mount tmpfs for containers by setting emptyDir.medium field to “Memory”, where data is stored in memory, much faster than local and network storage. But during node restart, memory data is cleared; if stored on disk, data remains after restart. Additionally, memory used by tmpfs is counted in container’s total memory usage, subject to system Cgroup limits.

emptyDir is initially designed to serve applications as cache space or store intermediate data for quick recovery. However, this doesn’t mean all users meeting above requirements are recommended to use emptyDir. We need to judge whether to use emptyDir based on actual business characteristics. Because emptyDir space is located on system root disk and shared by all containers, Pod eviction operations will be triggered when disk usage is high, thus affecting business stability.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: test-container

image: ubuntu

volumeMounts:

- name: my-volume

mountPath: /data

volumes:

- name: my-volume

emptyDir:

medium: Memory

Semi-Persistent Storage

Common semi-persistent storage is mainly hostPath volumes. hostPath volumes can mount files or directories from host node file system to specified Pods.

For ordinary users, such volumes are generally not needed, but for many Pods that need to obtain node system information, they are very necessary. For example, hostPath usage examples:

- Some Pod needs to get logs of all Pods on node, can access stdout output storage directory of all Pods through hostPath, such as

/var/log/podspath. - Some Pod needs to collect system-related information, can access system’s

/procdirectory through hostPath.

When using hostPath, besides setting required path attribute, users can optionally specify types for hostPath volumes, supported types include directories, character devices, block devices, etc.

hostpath Considerations

- Pods using the same directory may have different directory contents due to being scheduled to different nodes.

- Kubernetes cannot consider resources used by hostPath during scheduling.

- After Pod deletion, if no special handling is done, data written to hostPath will remain on node, occupying disk space.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: test-container

image: ubuntu

volumeMounts:

- name: my-volume

mountPath: /data

volumes:

- name: my-volume

emptyDir: {}

Persistent Storage

Persistent storage support is a necessary feature for all distributed systems.

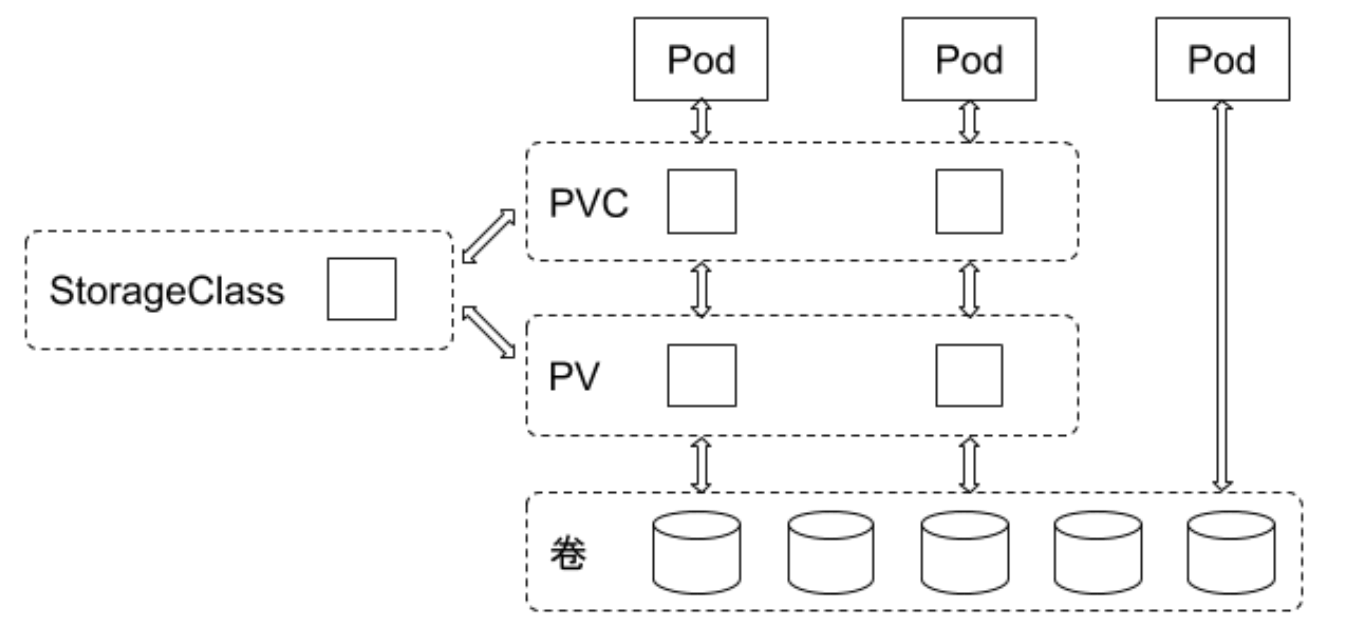

For persistent storage, Kubernetes introduces concepts of StorageClass, Volume, PVC (Persistent Volume Claim), PV (Persistent Volume) to manage storage independently of Pod lifecycle.

Kubernetes currently supports persistent storage including various mainstream block storage and file storage, such as awsElasticBlockStore, azureDisk, cinder, NFS, cephfs, iscsi, etc., which can be broadly categorized into network storage and local storage.

StorageClass

StorageClass is used to indicate storage types. Different storage types can provide services to users through different StorageClasses.

StorageClass mainly contains storage plugin provisioner, volume creation and mount parameters fields.

PVC

Created by users, representing user storage requirement declarations, mainly containing required storage size, storage volume access modes, StorageClass types, etc. Storage volume access modes must be consistent with storage types.

- RWO: ReadWriteOnce, volume can only be mounted on one node, with read-write properties

- ROX: ReadOnlyMany, volume can be mounted on different nodes, with read-only properties

- RWX: ReadWriteMany, volume can be mounted on different nodes, with read-write properties

PV

Created in advance by cluster administrators or dynamically created based on PVC application requirements, representing real storage space in system backend, which can be called volume space.

Create a PV in k8s to represent external system storage space.

Storage Object Relationships

Users create PVCs to request storage. Controllers create volumes on storage backends and then create PVs through StorageClass and size declarations requested by PVCs. Pods reference storage by specifying PVCs.

Pod specifies which PVC to use, PVC associates with PV, PV corresponds to backend storage.

Which plugin-controlled backend storage specifically needs to be created is controlled by StorageClass specified in PVC.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: test-container

image: ubuntu

volumeMounts:

- name: my-volume

mountPath: /data

volumes:

- name: my-volume

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: my-pvc

Production Practice Experience Sharing

Different media type disks need different StorageClass settings for user differentiation. StorageClass needs to set disk media types for users to understand storage properties.

In local storage PV static deployment mode, each physical disk should create only one PV rather than dividing into multiple partitions to provide multiple local storage PVs, avoiding I/O interference between partitions during use.

Local storage needs to be used with disk detection. When cluster deployment scales up, local storage PVs in each cluster may exceed tens of thousands. Disk damage will be frequent events. At this time, specific processing is needed for node disks and corresponding local storage PVs when disk damage and disk loss are detected, such as triggering alarms, automatic node cordoning, automatic user notification, etc.

For disk management of nodes providing local storage, flexible management and automation are needed. Node disk information can be unified and centrally managed. Add deployment logic in local-volume-provisioner. When containers start, pull disk information that nodes need to provide local storage, such as disk device paths, providing local storage in Filesystem or Block mode, or whether to join certain LVM virtual groups (VG), etc. local-volume-provisioner formats disks or joins certain VGs based on obtained disk information, forming automated closed loop for local storage support.

Recommendations:

- To avoid data loss, using persistent storage volumes is recommended. When using persistent storage volumes, backup and recovery strategies should be considered, as well as volume size and performance requirements.

- Avoid using semi-persistent storage volumes (EmptyDir) to store important data within Pod lifecycle. If data sharing between containers is needed, use persistent storage volumes.

- For scenarios requiring temporary data storage, temporary storage volumes are recommended. These volumes automatically clean up when Pod lifecycle ends, requiring no manual cleanup.

- When using storage volumes, ensure your container images have necessary file systems and tools to access data in volumes.

- If custom storage volumes are needed, ensure plugins or external storage systems are properly configured.

- When defining storage volumes and PVCs, use meaningful names for easy identification and management.

- When setting storage classes, consider your application’s performance and reliability requirements. Different storage classes may have different performance and reliability characteristics.

- When using storage volumes, follow Kubernetes best practices and security guidelines.

Exclusive LocalVolume

Besides the three storage volume types supported by Kubernetes, LocalVolume can also be used to create exclusive local storage volumes. LocalVolume is a storage type in Kubernetes that associates Pods with directories or devices on local disks to provide exclusive storage space. LocalVolume is suitable for applications requiring local disk access, such as databases or file servers.

Here’s an example YAML configuration using LocalVolume:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: test-container

image: ubuntu

volumeMounts:

- name: my-volume

mountPath: /data

volumes:

- name: my-volume

local:

path: /mnt/disks/data

In the above example, we associate Pod with local disk directory at path /mnt/disks/data to provide exclusive storage space. We use local type to specify volume type and specify path as path field value.

Unlike other storage volume types, LocalVolume cannot be shared by multiple Pods. This is because file systems and data on local disks can only be accessed by one Pod. If data sharing between multiple Pods is needed, other storage volume types should be used, such as NFS or iSCSI.

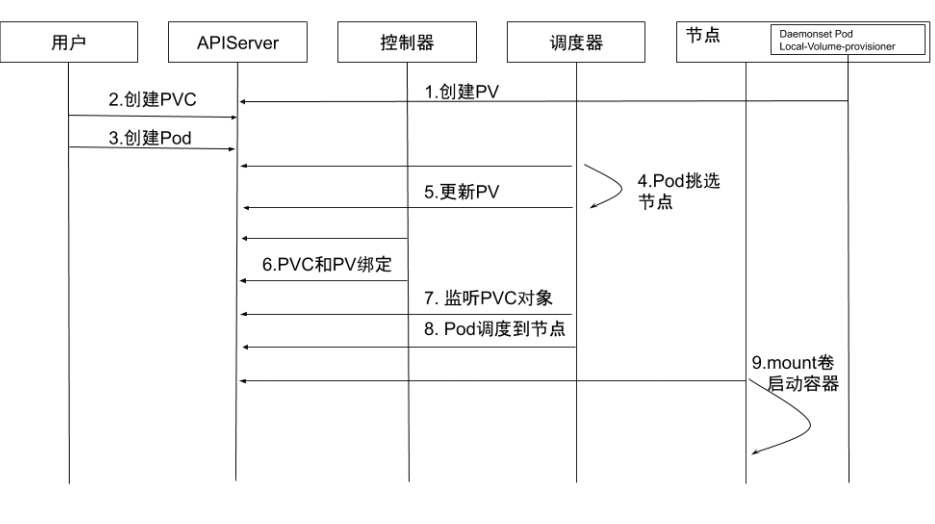

- Create PV: Create local storage PVs through

local-volume-provisioner DaemonSet. - Create PVC: User creates PVC. Since it’s in pending state, kube-controller-manager won’t perform any operations on this PVC.

- Create Pod: User creates Pod.

- Pod node selection: kube-scheduler starts scheduling Pod, selects PVs meeting conditions through PVC’s

resources.request.storageand volumeMode, and selects appropriate node for Pod. - Update PV: kube-scheduler sets PV’s

pv.Spec.claimRefto corresponding PVC and setsannotation pv.kubernetes.io/bound-by-controllervalue to “yes”. - PVC and PV binding:

pv_controllersynchronizes PVC and PV status and binds PVC and PV. - Listen to PVC object: kube-scheduler waits for PVC status to become Bound.

- Pod scheduling to node: If PVC status becomes Bound, scheduling succeeds; if PVC remains in pending state, it will reschedule after timeout.

- Mount volume and start container: kubelet listens to Pod scheduled to node, performs mount operations on local storage, and starts container.

Dynamic Local Volume

Dynamic Local Volume is a storage volume type in Kubernetes that can dynamically create and delete local storage volumes to provide exclusive storage space. Unlike other storage volume types, Dynamic Local Volume doesn’t require manually creating local storage volumes in advance but dynamically creates local storage volumes when Pods are created. This makes using local storage volumes in Kubernetes clusters more flexible and convenient.

Dynamic Local Volume can be implemented through Kubernetes plugins or local storage systems. Before using Dynamic Local Volume, LocalVolumeDiscovery plugin needs to be set up in Kubernetes cluster first. LocalVolumeDiscovery plugin is used to automatically discover and create local storage volumes for association with Pods.

CSI drivers need to report storage resource information on nodes for scheduling use.

But different machine manufacturers have different reporting methods.

For example, some manufacturers' machine nodes have multiple storage media like NVMe, SSD, HDD and hope to report these storage media separately.

This requirement differs from other storage type CSI driver interface requirements. Therefore, how to report node storage information and how to apply node storage information to scheduling currently has no unified opinion.

Cluster administrators can make some code modifications to open-source CSI drivers and scheduling based on actual node storage conditions, then deploy and use them.

Local Dynamic Mount Process

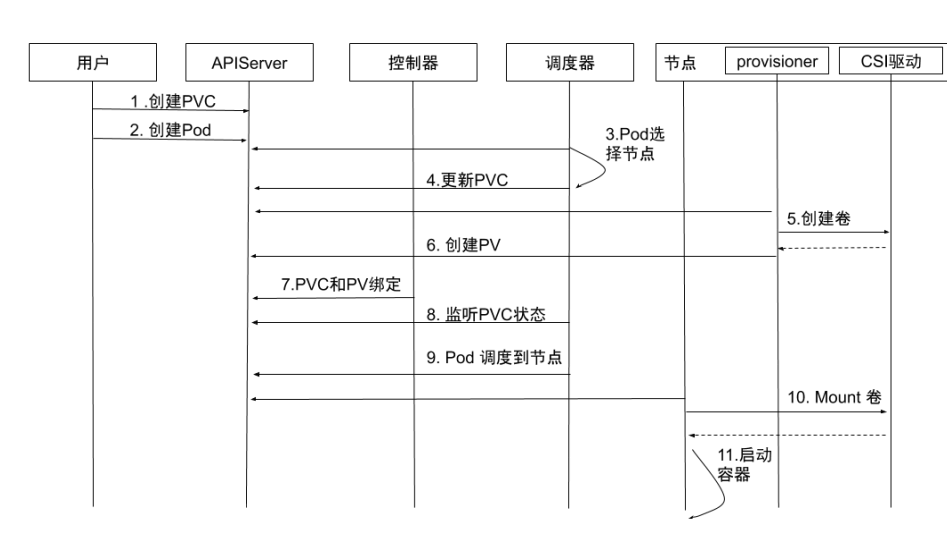

- Create PVC: User creates PVC, PVC is in pending state.

- Create Pod: User creates Pod.

- Pod node selection: kube-scheduler starts scheduling Pod, selects nodes meeting conditions through PVC’s pvc.spec.resources.request.storage, etc.

- Update PVC: After selecting node, kube-scheduler adds annotation containing node information to PVC:

annotation:volume.kubernetes.io/selected-node: <node name>. - Create volume: Container external-provisioner running on node listens to PVC with annotation related to this node and requests volume allocation from corresponding CSI driver.

- Create PV: After PVC obtains required storage space, external-provisioner creates PV with

pv.Spec.claimRefset to corresponding PVC. - PVC and PV binding: kube-controller-manager binds PVC and PV, changing status to Bound.

- Listen to PVC status: kube-scheduler waits for PVC to become Bound state.

- Pod scheduling to node: When PVC status is Bound, Pod is truly scheduled successfully. If PVC remains in Pending state, it will reschedule after timeout.

- Mount volume: kubelet listens to Pod scheduled to node and performs mount operations on local storage.

- Start container: Start container.

Local Dynamic Challenges

If disk space is used as a storage pool (like LVM) for dynamic allocation, then in the use of allocated logical volume space, there may be I/O interference from other logical volumes because underlying physical volumes might be the same.

If PV backend disk space is an independent physical disk, then I/O won’t be interfered.

Rook

Rook is an open-source distributed storage orchestration system for cloud-native environments, currently supporting storage systems like Ceph, NFS, EdgeFS, Cassandra, CockroachDB. It implements an automatically managed, automatically scaling, automatically healing distributed storage service.

Rook supports automatic deployment, startup, configuration, allocation, scaling/shrinking, upgrade, migration, disaster recovery, monitoring, and resource management.